When we asked members what subject they’d like to see us cover in our bondage and photography tutorials, one suggestion really caught my eye: how to shoot better bondage photos with absolutely minimal kit, specifically with a smart phone. It was interesting because it’s the most accessible way to start shooting; huge numbers of us have smart phones with pretty decent cameras on them.

It was also interesting because I didn’t have the faintest idea how to do it. I’ve been a professional bondage photographer for 18 years, and I’ve shot a few bits and pieces on my iPhone, but never even attempted a Restrained Elegance bondage stills set. I mostly use my phone for snapshots, pictures in the mountains, panoramas and quickie videos. So I couldn’t just switch into lecturer mode and pass on what I’d learned so far: I’d have to treat it like an experiment. How DID one shoot better photos with a smart phone?

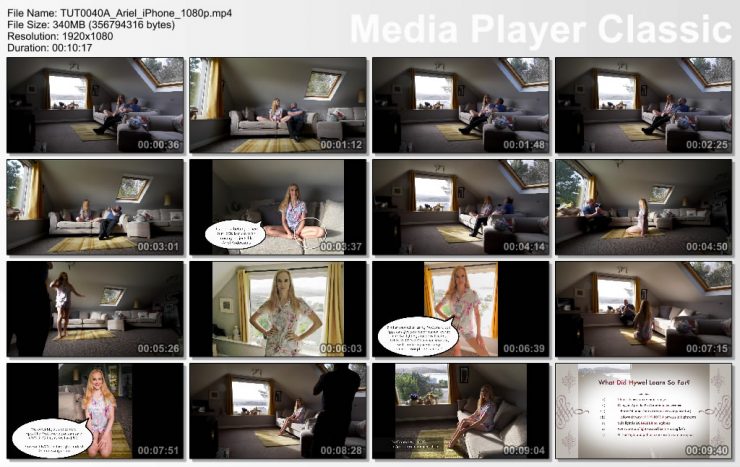

Fortunately I have an in-house expert, a photographer who sells sets of photos shot on a smart phone: Ariel Anderssen. As you may know, Ariel runs an OnlyFans page sharing behind the scenes news and sexy selfies on a daily basis- and a lot of what she shoots, she shoots on her iPhone. We sat down together to see what we could do with just a room with a bit of space, some rope, some natural light and my iPhone. No Restrained Elegance cameras, lenses or lighting rigs allowed! (Except for the behind the scenes cameras we were filming our experiment on – and those I just left on auto settings and didn’t grade the footage so you could get a feeling for how the light in the room really looked).

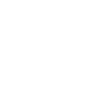

The light was changing rapidly with the sun coming and going, which is tricky enough on a camera with a large sensor. Large sensors means large pixels, which means higher full-well capacity. That is, it can register a brighter light before it burns out to white, relative to how dark the shadows are. Smartphone sensors are small – 1/3rd of an inch in the case of my iPhone SE. Its full specs are 12 MP, f/2.2 aperture, 29mm lens (35mm equivalent focal length- it’s actually a very much shorter lens than that, about 4 mm, which is the reason the images have very deep depth of field compared with a large sensor camera), 1/3″, 1.22µm pixel pitch, PDAF (which means it has nice phase detect autofocus).

My camera of choice for these situations would be a Sony A7RIII: 42 MP, choice of lenses (I’d typically try a 55mm f/1.8 in these circumstances), 35mm sensor, 4.5µm pixel pitch, PDAF. There’s a nice page with a comparison of sensor sizes So the Sony has many more pixels, but more importantly each pixel is much bigger- about 20 times the area. That means each pixel can probably hold about 20 times as many electrons, and register a signal 20 times as bright before burning out. (The exact numbers will depend on all sorts of other technical factors. But the sheer size of the pixels is always going to limit the dynamic range of the smartphone).

So my normal lighting patterns and shooting habits were just not going to work. We were going to have to work the model and the position around the limitations imposed by the camera’s dynamic range.

Ariel doesn’t think in technical terms, but she knows when a photo of herself is looking good and when it is looking crap on the phone screen. How does she work with the light?

She explained her three rules of thumb.

1) Side light looks appalling.

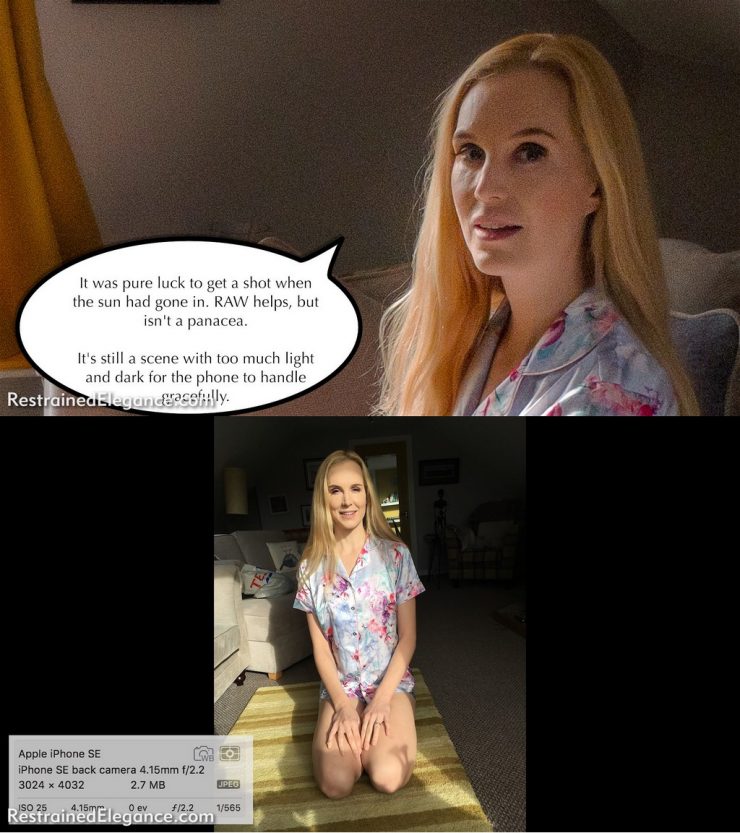

2) Full-on-facing-the-front-light is best. She likened that to the ring-flash effect. Find a big window, put the phone in it pointing at the model, and she sits in the pool of light cast by the window. Like a ring-flash, this tends to eliminate shadows (which is flattering). There’a a reason why a lot of models self-shooting on a phone use a ring-light.

3) Back-lit is the fallback option, but you need some sort of exposure compensation, either pulling it up in camera as you take it, or in post afterwards.

As is good practice, we figured out what to do with the lighting BEFORE tying Ariel up. This first part video is us doing that, and coming up with some lessons learned.